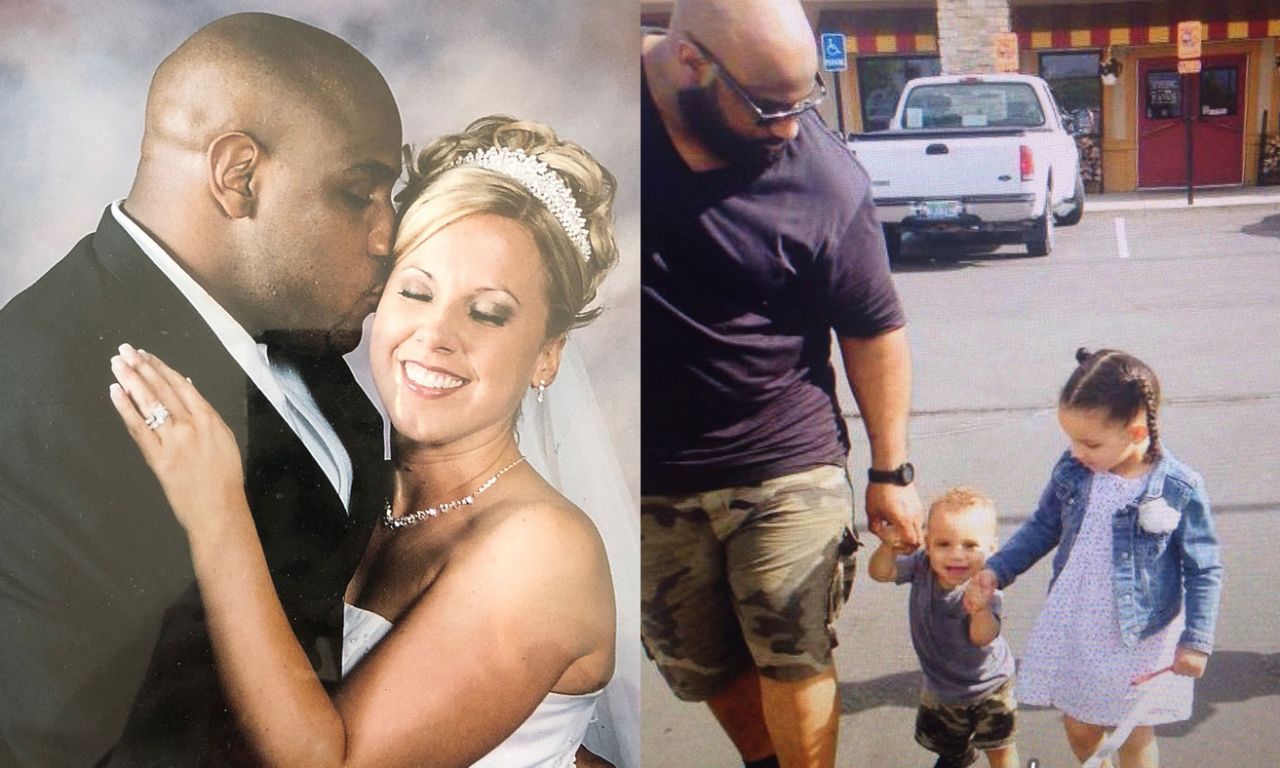

Football player Jon McCall and his wife, Sara, who is caring for her husband as he suffers complications of CTE. (Photo: Courtesy of Sara McCall)

From Yahoo Lifestyle, 11/2018

When Sara Koski met Jon McCall, a professional Arena Football League player, she had no interest in becoming an athlete’s girlfriend. But sure enough, that’s what happened.

“For about six months, he kept calling and trying to get me to go out with him, and I was like, ‘I don’t know. We can be friends, but I’m not really into this whole professional football thing,’” she tells Yahoo Lifestyle. But eventually, she decided to give him a shot.

“We were literally inseparable after that,” Jon’s now-wife, Sara McCall, says. “I don’t even know how that happened.”

Now, 15 years later, Sara is caring for Jon as he suffers from what doctors believe is chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) — the brain disease, common with football players, that’s caused by repeated concussions. Although she has no regrets, she’s sharing her story — through a recent Facebook Fundraiser post that’s pulled in more than $12,000 so far, and with Yahoo Lifestyle — as a warning to others considering a life in contact sports.

Like many a professional athlete’s partner before her, Sara took a flexible job as a waitress and went to all the games she could. She loved watching, but always had a hard time witnessing Jon get hurt. He ended up having 20 surgeries throughout his career, and he once estimated that he had had about 100 concussions. At one point, she asked him if he would quit. He would not.

“I’m worried that I’ll end up resenting you,” he told her. “This is my life. This is what I was born to do.”

A difficult diagnosis

Eventually, however, after a career that took Jon through college at Central Michigan University, followed by a very short stint with the New England Patriots and then seven years in the AFL, he retired.

That’s when Sara and Jon started a new chapter together: They got married in 2007, got jobs at a mortgage company, and started a family, settling down in Troy, Mich. But by about 2012, Jon started showing signs of mental distress. He had severe anxiety, memory loss, and difficulty eating.

“At the time, we didn’t know it was CTE, and for many years, he was bounced in and out of the hospitals in the Michigan area and misdiagnosed with many different conditions that years later we found out … he truly didn’t have,” Sara tells Yahoo Lifestyle, adding that a doctor at the Henry Ford West Bloomfield Hospital was able to make a pretty certain diagnosis of CTE based on Jon’s other collective diagnoses — dementia, PTSD, severe social anxiety, severe depression, and ADHD. “It was a relief to finally know what we were really dealing with,” she says.

Since 1928, doctors have known that boxers could experience long-term effects of repeated brain trauma. But it wasn’t until 2002 that pathologist Bennet Omalu began to study the brains of deceased football players. Today, after the high-profile deaths of many NFL players, a big settlement by the NFL, and the Will Smith movie Concussion, it seems like everyone knows something about CTE. The brain disease is caused by repeated concussions or subconcussive impacts, which cause the release of what are called tau proteins that, in turn, cause brain cell death.

Technically, CTE cannot be clinically diagnosed until after a patient’s death, so doctors can treat the living based only on their collective symptoms. As researchers learn more about the disease, it’s becoming clear that the scope of people affected goes beyond wealthy former NFL players and extends to those who play less lucrative sports, who played in high school and college, as well as military veterans. A study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association showed that 110 out of 111 brains of deceased NFL players and 48 out of 53 college football players had CTE. (But that was from a limited sample, from brains donated by surviving families who likely already suspected CTE, so it’s not seen as an accurate statistic of the prevalence of the disease. But it’s still a startling number.)

Sara wants to share her story in the hopes that she can prevent future generations from adding to those numbers, possibly by dissuading parents from letting their kids play football to begin with. “Even if it’s just one mom reading the article and saying, ‘Oh my God, I didn’t know this,’” she says.

After 10 years at his job, Jon was finally forced to quit because of his illness. His dementia is now so severe that he can’t drive himself anywhere, nor can he keep track of the 13 medications he’s taking. It’s led to many moments of defeat and desperation for Jon; there has even been a suicide attempt.

“I cannot tell you how many times I know that I have saved my husband’s life, as he wanted the pain and the confusion to just stop,” Sara says.

The toll CTE can take on family members is great, says Lisa McHale, the director of family relations at the Concussion Legacy Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to the study, treatment, and prevention of brain trauma. It’s a difficulty that McHale experienced firsthand, having lost her own husband, former NFL player Tom McHale, to the disease when he was just 45.

“Their presentation [of symptoms] tends to begin with the mood and behavioral issues, which can be very, very challenging,” McHale tells Yahoo Lifestyle. That’s when people might notice their previously gentle loved one developing a short fuse, or see a responsible father developing a gambling or drinking problem.

“Later, it’s very common to develop memory and executive function difficulties, so holding down jobs is difficult,” she says. “Memory issues in later age can be very problematic for people taking care of elderly parents. Just imagine that in a spouse, whom you’re counting on to help support the family.”

McHale has seen families deal with financial crisis as a direct result of CTE, with spouses of those affected having to either take on extra jobs or quit them altogether to become full-time caregivers.

For Sara, the work crisis began when she had to start missing days in order to take her husband to doctor’s appointments and care for her family; this past June, Sara was fired — she believes unfairly — and has since filed complaints with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) and the Department of Labor, adding to her stress level.

Mounting medical bills

Even though COBRA payments cover the McCalls for three months, the family is now facing a pileup of medical costs. For most of October, Jon has been hospitalized in Indiana, three-and-a-half hours from their home, after a negative reaction to one of his medications. (Although there is no proven treatment for CTE, he undergoes several experimental treatments for his symptoms, including human-growth hormone injections.) He has special glasses to help with his sensitivity to light. He had also experimented with hyperbaric oxygen chamber treatment, but the expense — $8,000 a session — ensured it didn’t last long. Sara turned to a GoFundMe campaign for help last year, and this month raised more funds through her Facebook post.

“There were always tons of people around with their hands out when he played football, and he never ever said no,” she says of Jon’s generosity, and now his financial position has flipped. Until recently, Sara and Jon were financially supporting their parents, as well. Now they hope that some of the people they helped when they were able can, in turn, help the McCalls as Sara searches for a new job.

Jon’s brief time in the NFL did make him a part of the CTE lawsuit against and settlement with the organization, but, Sara says, the settlement doesn’t cover people living with the disease, since the clinical diagnosis can be made only after death.

Either way, a settlement from the NFL wouldn’t mean much to Sara.

“How do you put a number on my husband waking up and not knowing who I am, or not knowing who our son is, at 41 years old?” she asks. “Our son walks around — he’s 4 — and he’s like, ‘Is it Daddy’s good brain today, or is it daddy’s football brain today?’ He’s been doing that since he was 3.”

What may help Sara and others like her, McHale says, is establishing a connection to other family members of people with CTE. “I think there really is no substitute for that kind of interpersonal, one-on-one support, of somebody who understands and somebody who has been there,” she says.

Although the prognosis for Jon isn’t great, Sara tries to focus on the positive.

“A lot of men are just killing themselves because they can’t figure out what’s going on,” she says. “They give up, and those families are losing them completely. I’m lucky to have what I have now. We just take every day, and treasure as much as we can, because we don’t know what tomorrow will be like.”