From Yahoo Lifestyle, May 2, 2018

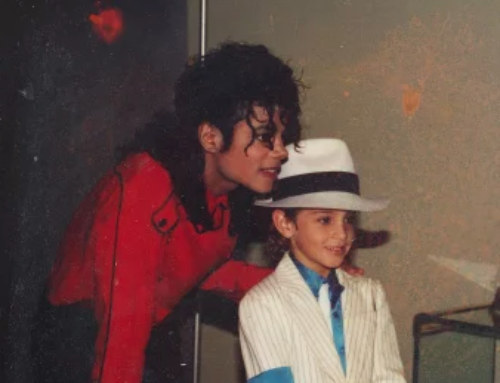

Amanda Knox interviewing Amber Rose. (Photo: Broadly/Amanda Knox Reports)

Hester Prynne had to stand on a scaffold in the middle of town, wearing her red letter “A” for adultery in the novel from which the new Broadly Facebook series The Scarlet Letter Reports gets its name. Compared to series host Amanda Knox and her interview subjects, you might wonder if Hester got off easy.

In the series, which premiered Wednesday morning, Knox talks to women about the public shaming and abuse they experienced in the media and online after daring to speak up for themselves while also being female. In the 10-minute segments she sits down with Anita Sarkeesian, the feminist video blogger who was a target of Gamergate abuse; Amber Rose, who has been badmouthed by exes Kanye West and Wiz Khalifa; Mischa Barton, who took her exes to court for their threats of revenge pοrn; Daisy Coleman, the Missouri teen bullied by an entire town after she was date raped; and Brett Rossi, the pοrn star who has sued ex-fiancé Charlie Sheen for assault.

“I’m looking at women who’ve all had very different experiences, but they all have echoes of the same problem,” Knox tells Yahoo Lifestyle of her subjects. That problem is the way society simultaneously seχualizes women for profit and then vilifies them for it.

Yeah, Amanda’s Been There

Knox isn’t exactly approaching this as an objective journalist. In the show, she addresses the way police, prosecutors, and the media used her own seχuality as proof that she murdered her roommate Meredith Kercher in Perugia, Italy, in 2007. She was acquitted of all charges upon appeal in 2011, and again by the Italian Supreme Court in 2015. Since then, she has been working as a writer and advocate for the wrongly convicted. She pitched the idea for The Scarlet Letter Reports (at first simply as an article for Broadly) knowing she would bring her own context to the subject.

“This isn’t going to be an interview, this is going to be a conversation between two women who have been there,” she says. “I can’t pretend I’m not me.”

In the first episode, Knox curls up on Sarkeesian’s couch and nods knowingly as she listens to her tales of being digitally edited into pοrnography and receiving graphic death threats.

“As someone who has been vilified in the media, [I know] it takes a lot of courage to be willing to sit across from me and say, ‘Hey, I’ve been there and I see you and I hear you,’ ” Knox explains. “That’s what the women said to me, as much as I was saying that to them.”

In the second episode, she and Rose bond over what it’s like to be torn apart by the media over having sex, while men simply get congratulated. After their chat, Rose gave Knox her number and a “Slut” cap, and they’ve been texting ever since.

SIuts: A Primer

Leora Tanenbaum, author of I Am Not a SIut: SIut-Shaming in the Age of the Internet, sees the direct line between Knox and her interview subjects. It’s part of the seχual double standard that has existed since the time of the Hebrew Bible, she says.

“SIut-shaming is a way for men in power (and also for women in power) to categorize some groups of women who are perceived to be overly seχualized, who are perceived to be violating norms of femininity, to keep them in their place and punish them,” she tells Yahoo.

These days, women have felt freer to embrace their seχuality, and social media has given them the means to share it, Tanenbaum says. This has, sadly, meant more women than ever are getting branded with that scarlet letter. Case in point, reporters picked up the “Foxy Knoxy” nickname that plagued Knox during her trial from her MySpace page.

“Obviously not everybody is going to be accused and charged with murder,” she says. “That is a very extreme example. But you exert your seχual agency, you’re not ashamed of it, you’re public about it, and you will be judged, shamed, and policed.”

Be Like Monica

Though she started working on The Scarlet Letter Reports before the #MeToo movement really took off last year, Knox says it’s made people ready to hear these stories. If the show gains traction, there are many other people she’d like to sit down with.

“So many women were on my wish list,” she says. “The one person who has been a huge inspiration and model to me has been Monica Lewinsky. … They totally destroyed her life, and the fact that she was able to build herself back up and make legitimate contributions to society and speak to her experience with so much compassion and authority — she is such a model to me.”

Knox and her first five subjects are all at different stages of building themselves back up, too. Rose, for example, said she truly doesn’t care about how the media portrays her anymore.

“That’s amazing,” Knox says, marveling at Rose’s peaceful attitude. “For me, I get to work. I spend a lot of time thinking and then meta-thinking, and I get to work.”

The victims aren’t the only ones who have work to do, of course. Tanenbaum has some thoughts on how everyone can start reshaping the vernacular surrounding women. Step one is to stop calling anyone a “sIut” or any of its synonyms.

“I’m not advocating censorship, but I am advocating mindfulness,” she says. “Using those words adds to this attitude that it’s OK to otherize women, that it’s OK to use derogatory language. I think it’s important as a first step forward to just never use these words at all.”

From Tabloids to Policy

When Knox pitched this project, she wanted to take the tabloids to task for exploiting salacious stories about women. The trick is not to become part of that exploitation as she asks women to retell these stories all over again for her show.

“What I’m hoping that people get out of this is they look at the evidence and then they say, ‘I’m seeing a human being; I’m not seeing this object, the gold digger, or the sIut, therefore I’ve been lied to,” she says. “If you scrap someone’s context and make them into two-dimensional versions of themselves, you are sacrificing truth in the process. That doesn’t just affect the people that are in the media. It affects all of us.”

Tanenbaum explains how both the famous and everyday cases of the seχual double standard wind up having an impact on all women.

“These attitudes about women’s seχual agency affect public policy about birth control, about abortion,” she says. “They affect the mindset of juries deciding seχual assault cases. This is such a bigger problem than that girl over there and that woman over there.”

What Knox wants — and this may be a tall order for a show told in 10-minute segments — is to make people ask questions about the attitudes many have taken for granted. That begins by giving women control over their own narratives.

“We’re all healing by adding our voices to the chorus of voices of other people who are authoring our experiences,” she says, “hoping that we are assuming an authority over ourselves.”