For Ancestry.com

The 1930s marked a dark time. Just as the Nazis were sweeping through Germany, countries were tightening their immigration policies in the wake of the Great Depression.

The United States, for instance, kept strict quotas on immigrants’ country of origin. Only 124,000 German Jews were allowed to enter between 1938 and 1941.

Thus, Jewish refugees with the resources to flee went to some places you wouldn’t necessarily expect to find Jewish communities.

The Dominican Republic

In July 1938, 32 countries convened at the Evian Conference in France to discuss placement of Jewish refugees. Most countries, including the U.S. and Great Britain, refused to increase their quotas.

Dominican President Rafael Trujillo announced that his country would accept 100,000 Jews and donate 26,000 acres of farmland in the town of Sosua, in exchange for financial assistance from other countries.

This act of apparent generosity happened just a year after Trujillo was responsible for the massacre of tens of thousands of Haitian immigrants. In the end, only somewhere between 600 and 800 Jews made their way to Sosua, but the country issued 5,000 visas that allowed those refugees to escape Nazi occupation.

Bolivia

Mauricio (Moritz) Hochschild, a German-Jewish mine owner, persuaded President Germán Busch to issue visas to 20,000 Jewish European refugees to boost the country’s economy. Their train trip from Chile to Bolivia became known as the “Express Judio.”

The American Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) helped fund their settlement on farmland, along with Hoschild’s Sociedad de Proteccion a los Immigrantes Israelitas (SOPRO), but many of the immigrants’ farms failed. Eventually, most emigrated, many crossing illegally into Argentina.

Shanghai

The Chinese city already had a small population of Jews who had emigrated from Iraq and Russia in previous decades, and because no visa was required for entry, 17,000 arrived from Germany in 1939. An additional 2,100 Polish Jews arrived in 1940-41.

The JDC was able to send financial assistance to the refugees initially, but the city was under Japanese occupation, and once the U.S. entered the war, sending money there became impossible.

In 1943, the immigrants were forced to stay in the Restricted Sector for Stateless Refugees but were relatively safe from the Japanese, despite the country’s alliance with Germany.

In the years after the war, civil unrest in China inspired many of the Jewish residents to leave for the U.S., which had finally eased its immigration restrictions.

Brazil

The country had a significant Jewish population since the 17th century, but several anti-Semitic laws and immigration restrictions were enacted in the early 20th century, including some banning Yiddish newspapers and Jewish organizations.

Many found that these laws weren’t enforced, however, and an estimated 17,500 Jews entered the country during the war.

Argentina

From the late 19th century until 1938, Argentina welcomed tens of thousands of Jewish refugees a year, most fleeing the Russian pogroms. Then the country legally closed its doors in an effort to remain neutral in the war.

The policy proved ineffective, though, as an estimated 43,000 refugees came in through bordering Bolivia, Chile, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay from 1933 through 1945. That’s more per capita than any other country during the war except for Palestine.

Many have heard about Argentina becoming a haven for former Nazi party members. And whether it’s a coincidence or not, Jews made up 5% of the 30,000 who disappeared during the country’s “Dirty War” of 1976. Yet today, Argentina remains the Latin American country with the largest population of Jewish people, 240,000 strong.

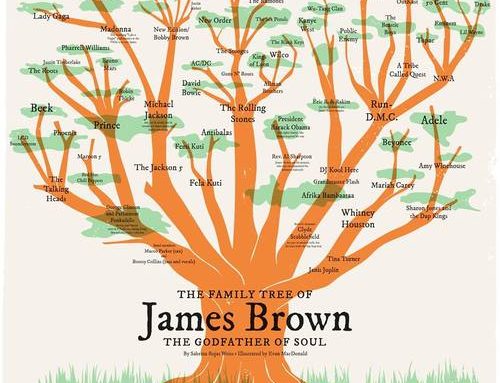

Did your family flee the Holocaust?

Ancestry has partnered with JewishGen, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC), the American Jewish Historical Society, and The Miriam Weiner Routes to Roots Foundation, Inc., to create the world’s largest online collection of Jewish historical records.

You can search through records of European Jewish communities predating World War II, as well as visa applications, Holocaust records, and passenger lists to trace your ancestors’ stories of tragedy and survival.

The research might lead you to surprising destinations as well.